In one of the earliest hints of "modern" living, humans 164,000 years ago put on primitive makeup and hit the seashore for steaming mussels, new archaeological finds show.

Call it a beach party for early man. But it is a beach party thrown by people who were not supposed to be advanced enough for this type of behavior. What was found in a cave in South Africa may change how scientists believe Homo sapiens marched into modernity.

Instead of undergoing a revolution into modern living about 40,000 to 70,000 years ago, as commonly thought, man may have become modern in stuttering fits and starts, or through a long slow march that began even earlier. At least that is the case being made in a study appearing in the latest issue of the journal "Nature" last week.

Researchers found three hallmarks of modern life at Pinnacle Point overlooking the Indian Ocean near South Africa's Mossel Bay: harvested and cooked seafood, reddish pigment from ground rocks, and early tiny blade technology. Scientific optical dating techniques show that these hallmarks were from 164,000 years ago, plus or minus 12,000 years.

"Together as a package this looks like the archaeological record of a much later time period," said study author Curtis Marean, professor of anthropology at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University.

This means humans were eating seafood about 40,000 years earlier than previously thought. And this is the earliest record of humans eating something other than what they caught or gathered on the land, Marean said. Most of what Marean found were the remnants of brown mussels, but he also found black mussels, small saltwater clams, sea snails and even a barnacle that indicates whale blubber or skin was brought into the cave.

Then they put them over hot rocks to cook. When the food was done, the shells popped open in a process similar to modern-day mussel-steaming, but without the pot.

Marean also found 57 pieces of ground-up rock that would have been reddish- or pinkish-brown. That would be used for self-decoration and sending social signals to other people, much the way makeup is used now, he said.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

"Truth is stranger than fiction" goes the old saying - and this blog seeks to make available to all as many stories and anectdotes as possible that highlight the strange, interesting and, sometimes, funny lives of ordinary and not-so-ordinary people down the ages, as well as share some difficult-to believe tidbits of information. Enjoy!!!

Facebook Badge

Labels

- 'Frog marriage' to please rain gods in Nepal (1)

- 'THE NATIONAL' ABU DHABI AND 'THE TRIBUNE' NORTH INDIA (1)

- 'Veiled' shock: Bride turns out to be a boy (1)

- 'What are you staring at?' (1)

- "CITY AUTHOR PENS RECORD" - SHARING THE NEWS ITEM WHICH WAS PUBLISHED IN YESTERDAY'S 'DAINIK JAGRAN' NEWSPAPER ('CITY PLUS' SUPPLEMENT) (1)

- "Deceivers" can be purchased online in a downloadable (Kindle edition) version (1)

- 000 pounds in aunt's grave (1)

- 100-year-old eats 30 bars of chocolate a week (1)

- 11month baby girl helps unconscious mum by answering cell phone... (1)

- 2010 : My first book released....September 3 (1)

- 2011 : 6 books published and 1 under publication.... (1)

- 2013 (1)

- 2015 (2)

- 22 (1)

- 300-pound jail inmate complains being ill-fed (1)

- 4 births (1)

- 4 days (1)

- 54-year-old Japanese caught impersonating his 20-year-old son to take an exam (1)

- 55 (1)

- 700 pounds bill for 27-hour sex hotline chat... (1)

- 700-volt shock (1)

- A gathering of Elizabeths (1)

- A homeless woman sneaked into a man's house and lived undetected in his closet for a year... (1)

- A jumbo 'brake' (1)

- a record book published by Coca Cola India (1)

- A temple (1)

- Aliens have been visiting Earth for decades: Canadian expert (1)

- An article about my five books...published in eight months... (1)

- An electric battery that is more than two thousand years old? (1)

- and first political crime thriller) (1)

- Another newspaper story about my career as an author (1)

- Article about me: "Writing a new chapter at 50 plus"... (1)

- Article about my books and me in the national daily The Hindustan Times (1)

- ARTICLE ABOUT MY FIVE BOOKS IN THE TIMES OF INDIA (1)

- ARTICLES ABOUT MY BOOKS IN 'GULF NEWS' DUBAI (1)

- as author with most books on crime fiction in shortest time (1)

- AT THE TIMES GROUP BOOKS STALL...DELHI WORLD BOOK FAIR 2013...WITH TWO OF MY BOOKS (1)

- Australian man survives 12 (1)

- Baby boomers: 4 sisters (1)

- becomes Professor Tulsi at IIT Bombay (1)

- Big bums and felony don't mix (1)

- Book returned after more than 100 years (1)

- build your satellite and put it into orbit for $8K (1)

- Burdened by debt single mother postal worker lottery-winner now richer than kings... (1)

- Cat's yowling saves owner from fire (1)

- Celebrity Second Acts (1)

- Chinese cabbie helps thief rob own home... (1)

- Couple from 'Hell' wins lottery... (1)

- Cross-dressing maids add spice to Tokyo cafes (1)

- Day of pranks: Flying car fix (1)

- Dead father wins girl concert tickets (1)

- Dead man 'sends' holiday greetings (1)

- Dead man gets re-elected as mayor (1)

- delivers quadruplets (1)

- Dog guards owner's body for six weeks (1)

- Dr Tathagat Tulsi (1)

- Drinking to excess (1)

- Drivers fined for slow-drive (1)

- Each day's V-Day for Malaysia's 'odd couple' (1)

- Eatery makes you pay for food you waste (1)

- Eight book reviews of my new novel "Chief Minister's Mistress"..... (1)

- English 'Lord' puts life up for sale on eBay (1)

- Evolution 'driving women to become more beautiful' (1)

- Featuring for two consecutive years in the Limca Book of Records (2012 and 2013) (1)

- Fed up with politics (1)

- Fields of watermelon burst in China farm fiasco (1)

- Fighter jets chasing 'UFO' captured on video (1)

- flavoured newspaper (1)

- found in 2008... (1)

- Friday 13th safer than an average Friday (1)

- Gender imbalance (1)

- Girl on bottle goes topless as you guzzle (1)

- Gossip leads to nasty surprise for Czech couple (1)

- Got a wish? Offer a clock to Ghari Baba (1)

- Graveyard marriage for Ohio couple... (1)

- Gypsy predicted Brit couple's 4mln Pounds lottery win (1)

- Hello from China... (1)

- Hotel guest slapped with 5 (1)

- I feature in the Forbes 2014 list of Top 100 Celebrity Indian Authors (1)

- INDIA - raw and unplugged (1)

- Indian woman (1)

- Indonesian Book on Obama Sets Record for Thickest Book (1)

- Inmate arrested trying to get back in jail (1)

- Interview in Spectral Hues.....September (1)

- Israeli parents forget daughter at airport... (1)

- Japan's new first lady says she rode in a spaceship (1)

- Japanese woman wins over thief with tea (1)

- Judge okays college's ban on female teachers (1)

- Laid back film... (1)

- Laughing over comedy show lands man in jail (1)

- Lottery jackpot lands Canadian in jail (1)

- Love candles set hotel ablaze (1)

- makes tea (1)

- Man claims he was canned for too much 'waist' (1)

- man eats vote... (1)

- Man faces jail for having sex with sleeping wife (1)

- Man finds diamond ring inside candy (1)

- Man held for stealing his own van (1)

- Man hides 140 (1)

- Man in Guinness for getting hit by car... (1)

- Man offers Lamborghini as part of deal to sell 1.1million pounds home (1)

- Man seeks ride from detective after heist (1)

- Meet the toy-mad Brit who has a collection of two million Lego bricks (1)

- Meet the world's meanest boyfriend... (1)

- Millionaire to keep working as cleaner (1)

- Miss Singapore World resigns after lingerie fraud (1)

- Most bizarre complaints witnessed by travel agents (1)

- Mouse builds nest in Oregon ATM with USD 20 bills (1)

- Mustang: Lost in 1970 (1)

- My Author's Corner event at the Delhi World Book Fair (1)

- My fourth book (1)

- My interview in 'Suburb'.....September (1)

- My new book (my 16th release (1)

- My second novel: "The Inheritance" has been published (1)

- My three books (1)

- MY WEBSITE (1)

- Nagging really does wonders on men (1)

- Naked war breaks out between Germany and Poland (1)

- National Record Certificate: 2014.....Fastest published crime fiction author of India (fourth year in a row) (1)

- New Zealand school to ban birthday cakes (1)

- Nostradamus predicted his own death.....and even beyond. (1)

- Now (1)

- Parrot wakes up owner to shoot burglar (1)

- Police use tobacco spit to nab burglar (1)

- Robbery suspect has an identity crisis... (1)

- Scottish man sets new world record by running 259 ft with body set on fire (1)

- September 4 (1)

- Shoplifter gets run over twice by her getaway car (1)

- Spelling gaffe turns city into 'unwiped bottom' (1)

- The curious case of a missing cow (1)

- The first buyer of my second book - Shivangi Dhingra (1)

- The Lady's manor in Britain that was turned into a brothel... (1)

- The oldest language still in use (1)

- the screw or the screwdriver? (1)

- Thief crawls through mail flap (1)

- Thief deposits loot with victim (1)

- TIMES OF INDIA - "SPEED WRITER IN RECORD BOOKS" (ARTICLE IN YESTERDAY'S NEWSPAPER ABOUT MY BOOKS AND MY RECORD ENTRY IN THE LIMCA BOOK OF RECORDS) (1)

- Tragic coincidence (1)

- TWO RECENT NEWSPAPER REPORTS ABOUT MY WRITING CAREER (1)

- Two-timing US woman has twins from 2 men (1)

- UK cops hand out gun permits to 7-yr-olds (1)

- Unique missiles (1)

- US woman uploads divorce rant to YouTube... (1)

- Vandals taught a lesson...with verse (1)

- Vending machines that kill (1)

- Wackiest path to record books... (1)

- When diamonds become girls' worst friends (1)

- where devotees offer liquor to deity (1)

- Which came first (1)

- Winemaker's nose insured for $8 million... (1)

- Wishing everybody a very happy Holi. Enjoy the festival of colours. May your lives be always filled with beautiful colours and lots of laughter... (1)

- Wishing you a very happy Holi (1)

- Without a bath (1)

- Woman marries 7 times in 45 days (1)

- Woman passes driving test after 27 years and 450 lessons (1)

- Woman sues US zoo over splashing dolphins (1)

- Woman survives being shot in head (1)

- Woman's record-length fingernails broken in crash (1)

- World record for stripping down to your underpants (1)

- World record sandwich? Iranians eat evidence... (1)

- Would you have invested in this group? (1)

- WRITE UP IN THE 'LIMCA BOOK OF RECORDS' 2012 EDITION (1)

- Yesterday was Priti and my nineteenth wedding anniversary (1)

New mouse...

PREPARING FOR THE HIT...

Happy reading

These stories, anecdotes and information tidbits (presently 251 in number) have been compiled after extensive research over many years and from numerous sources. They go to prove - if proof were needed - that we live in a very strange world indeed. Happy reading!

Blog Archive

-

►

2017

(1)

- ► 03/12 - 03/19 (1)

-

►

2016

(2)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (2)

-

►

2015

(6)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (2)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (1)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (1)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

-

►

2014

(1)

- ► 04/06 - 04/13 (1)

-

►

2013

(4)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (1)

- ► 06/23 - 06/30 (1)

- ► 02/24 - 03/03 (1)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (1)

-

►

2012

(6)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (1)

- ► 09/30 - 10/07 (2)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (1)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (1)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (1)

-

►

2011

(18)

- ► 12/11 - 12/18 (1)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (1)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (1)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (1)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (1)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (1)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (1)

- ► 05/15 - 05/22 (2)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (1)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (1)

- ► 01/30 - 02/06 (1)

- ► 01/23 - 01/30 (1)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (1)

- ► 01/02 - 01/09 (4)

-

►

2010

(13)

- ► 10/17 - 10/24 (1)

- ► 10/10 - 10/17 (1)

- ► 10/03 - 10/10 (1)

- ► 08/29 - 09/05 (1)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (3)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (1)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (1)

- ► 06/06 - 06/13 (1)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (1)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (1)

-

►

2009

(29)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (3)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (1)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (1)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (3)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (1)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (3)

- ► 05/17 - 05/24 (2)

- ► 05/03 - 05/10 (1)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (1)

- ► 03/15 - 03/22 (6)

- ► 03/08 - 03/15 (2)

- ► 03/01 - 03/08 (1)

- ► 02/08 - 02/15 (2)

- ► 01/18 - 01/25 (2)

-

►

2008

(65)

- ► 12/21 - 12/28 (1)

- ► 12/07 - 12/14 (2)

- ► 11/23 - 11/30 (2)

- ► 10/12 - 10/19 (1)

- ► 09/21 - 09/28 (5)

- ► 09/07 - 09/14 (3)

- ► 08/24 - 08/31 (1)

- ► 08/17 - 08/24 (1)

- ► 08/10 - 08/17 (1)

- ► 08/03 - 08/10 (3)

- ► 07/27 - 08/03 (1)

- ► 07/06 - 07/13 (3)

- ► 06/29 - 07/06 (1)

- ► 06/08 - 06/15 (2)

- ► 06/01 - 06/08 (2)

- ► 05/25 - 06/01 (1)

- ► 05/04 - 05/11 (5)

- ► 04/20 - 04/27 (7)

- ► 04/06 - 04/13 (1)

- ► 03/23 - 03/30 (2)

- ► 03/16 - 03/23 (6)

- ► 03/02 - 03/09 (3)

- ► 02/24 - 03/02 (1)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (3)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (2)

- ► 01/20 - 01/27 (1)

- ► 01/13 - 01/20 (4)

-

▼

2007

(133)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (3)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (1)

- ► 12/09 - 12/16 (1)

- ► 12/02 - 12/09 (2)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (1)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (3)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (1)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (6)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (3)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (8)

- ▼ 10/14 - 10/21 (5)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (2)

- ► 09/30 - 10/07 (6)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (1)

- ► 09/16 - 09/23 (3)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (5)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (3)

- ► 08/12 - 08/19 (6)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (7)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (6)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (7)

- ► 07/15 - 07/22 (11)

- ► 07/08 - 07/15 (14)

- ► 07/01 - 07/08 (8)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (8)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (10)

That's me

My family and me

My wife and me (and some friends)

My wife and me and another friend...

That's me at my office desk

That's me as a kid

About Me

- Joygopal Podder

- I head fundraising in India for a leading international anti poverty development agency. Prior to this assignment, I worked for a leading child welfare organisation. Prior to this, I worked for an NGO looking after the elderly (type Joygopal Podder on Google search and you can view newspaper reports of various activites I have organised for the causes I work for). I moved to the "not-for-profit" sector after 15 years in industry. I am a freelance writer (my stories are used in text books of schools like Delhi Public School) and a Gold Medalist Law Graduate. I have a lovely family consisting of two talented and beautiful daughters and an interior designer-turned-marketing professional wife. I was born in London, worked for some time in the Middle East and now work in Delhi and live in the suburbs. I travel 15 days a month in India and abroad - and watch movies every weekend. I am maintaining the following blogs: http://compiledbyjoygopalpodder.blogspot.com http://mysteriesaroundus.blogspot.com http://noticeboardonanythingand everything.blogspot.com http://storiesbyjoygopalpodder.blogspot.com http://grandmothertales.blogspot.com http://stockmarketswithjoygopalpodder.blogspot.com

Picture of the year

LOST...AND FOUND?

Posting Letter

HOT DOG...

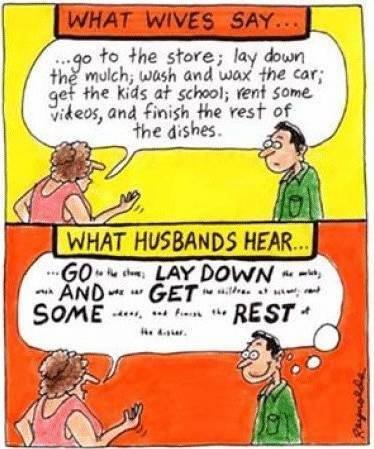

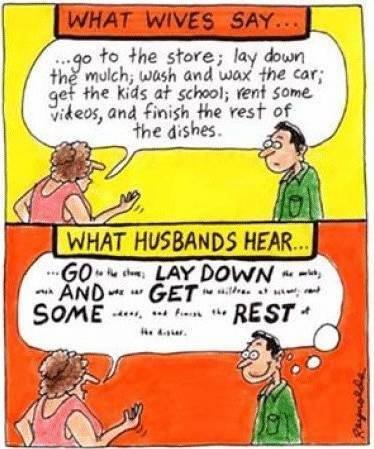

What wives say.....what husband's hear

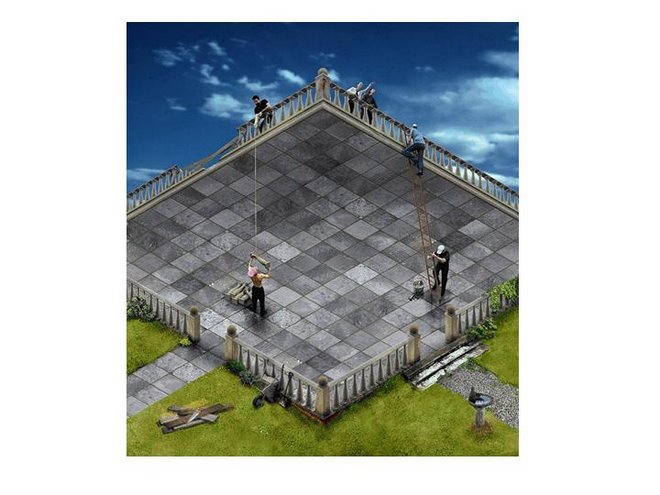

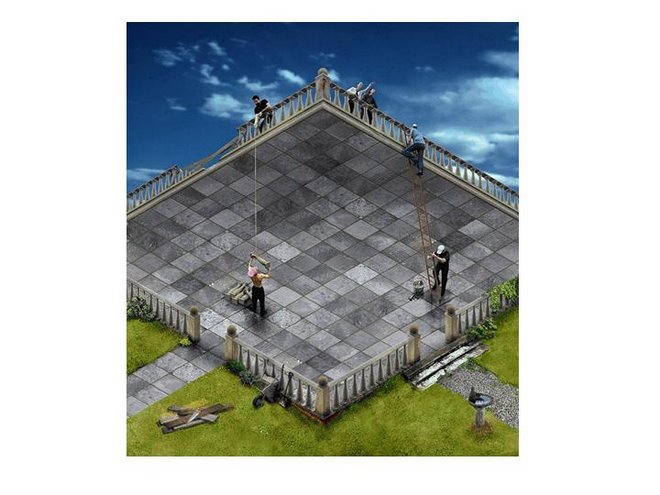

Illusion...which way is up?

The wizards and witches of Hogwarts

Satan's Work